The Partnership Paradox

17 Feb, 20267 minutes

The Partnership Paradox

Why Brilliant Lawyers Don’t Make Partner (And Why Average Ones Sometimes Do)

After thirteen years specialising in partner-level recruitment across London and the South East, I’ve witnessed something that initially seemed counterintuitive: some of the most technically brilliant lawyers I’ve known never made partner, while others, competent but unremarkable, sailed through to equity partnership within eight years. This isn’t a story about unfairness or corporate politics, though both certainly play a role. It’s about understanding that partnership selection operates according to a set of unwritten rules that most associates discover far too late in their careers.

The data paints a stark picture. UK law firms within The Lawyer UK 100 have increased partner headcount by 14% since 2022, yet partnership class sizes have been shrinking for two consecutive years. Kirkland & Ellis, which promoted 200 lawyers in 2024, has seen roughly 10% of that class disappear from the firm’s website or move elsewhere within a year, with the 2023 class showing an even steeper attrition rate of approximately 20%. Meanwhile, equity partner growth across the Am Law 200 contracted by 0.5% in the first nine months of 2025, while non-equity partnership grew by 6%.

What’s happening? Why are firms promoting fewer equity partners despite record profits: median PEP surging 23% in 2025, with larger firms seeing 31% increases? And more importantly for ambitious associates, what actually determines who makes it and who doesn’t?

The Uncomfortable Truth About Partnership Economics

Let me be blunt about something the managing partners won’t tell you: law firms don’t want to make you partner. Every new equity partner dilutes existing partners’ profit share. Every additional name on the partnership roster means existing partners take home slightly less, unless that new partner brings enough revenue to more than compensate for their share of profits.

The mathematics are straightforward. At UK top 50 firms, the gap between top and bottom equity has never been wider; top-end PEP jumped 18.6% to £1.38 million in recent figures, while the bottom dropped nearly 10% to £291,000. Junior partners are being squeezed as star performers pull further ahead. When the best-rewarded partnerships average £3+ million per equity partner, the partnership isn’t looking to dilute that with associates who can’t demonstrate a clear path to similar contribution.

I’ve had countless conversations with senior associates who genuinely believe that billing 2,400 hours and delivering excellent client work entitles them to partnership. It doesn’t. What entitles you to partnership is demonstrating that your economic value to the firm exceeds what the firm pays you, dramatically so. The title ‘partner’ isn’t recognition of past performance; it’s an investment in future revenue generation.

This is why non-equity partnership has exploded. Firms can grant you the title, keep you billing enormous hours, maintain your psychological investment in the firm, and crucially, avoid giving you a meaningful share of profits. It’s partnership theatre: you get the business card, but the economics remain fundamentally unchanged from senior associate level.

The Gender Partnership Gap

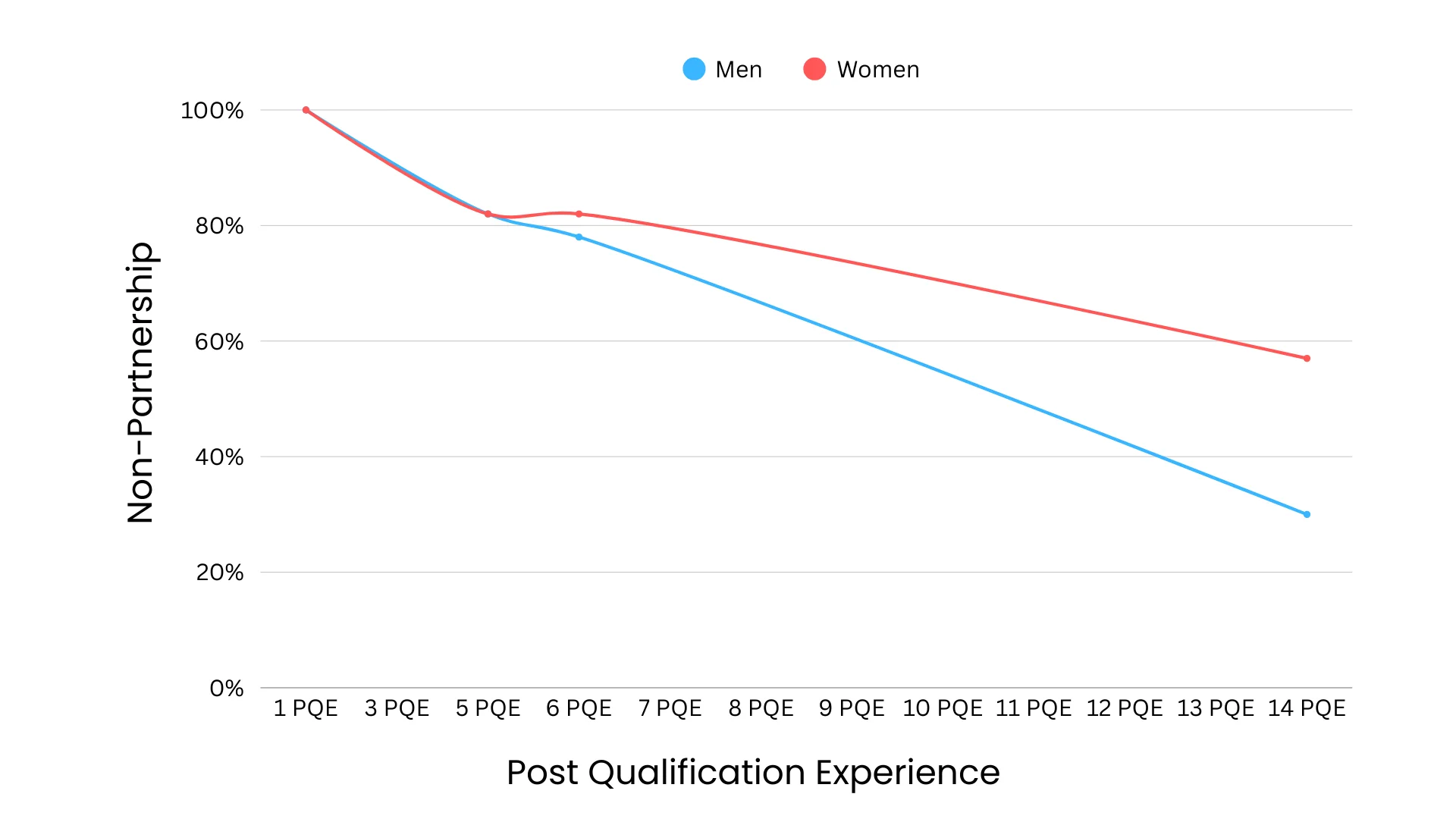

There’s a specific moment when partnership prospects diverge dramatically between male and female lawyers, and it’s earlier than most firms acknowledge. Research from Pirical shows that during PQE 5 to PQE 6, a 4% divergence opens up between the proportion of men and women promoted to partner. By PQE 10, 50% of men are still non-partners, while 76% of women remain in associate roles. The gap widens to 27% by PQE 14.

Figure 1: Gender Disparity in Partnership Progression. Source: Pirical research. Curves interpolated from published data anchors.

This creates a structural problem that perpetuates itself: more men in middle management means more men selecting the next cohort of partners, which skews further toward male candidates. Firms wanting to intervene effectively should target PQE 5, one year before the divergence starts.

In London’s litigation market, the figures are particularly stark. Women now constitute only 31% of litigation partners, down from a peak of 46% in 2022, and made up just 28% of lateral partner moves in 2025. The pattern is consistent: women are promoted to partner less frequently, leave partnership tracks earlier, and when they do make partner, more often receive non-equity rather than equity positions.

The Book of Business Myth

In the Am Law 200, firms typically require lateral partners to demonstrate between $1–3 million in portable business in major markets. But what constitutes ‘your’ business is subject to interpretation that would make a tax lawyer blush. I’ve seen candidates claim £2 million in portable business only to discover, upon joining a new firm, that perhaps £400,000 was genuinely attributable to their personal relationships. The rest was institutional client work that followed the firm’s brand, not the individual lawyer.

What actually matters:

- Client loyalty that transcends the firm. Do clients ask for you specifically, or do they contact the firm and you get assigned? If you left tomorrow, would they follow you or stay with your firm?

- Origination credit versus execution credit. Did you bring in the client relationship, or are you servicing someone else’s client? Firms credit origination far more heavily than execution.

- Growth trajectory, not just current revenue. A candidate billing £800,000 but growing 25% annually is more attractive than someone plateaued at £1.5 million.

- Client concentration risk. £2 million from one client is worth less than £1.2 million from eight. Lose that single relationship and your value to the firm collapses.

The hardest truth I tell candidates: if you haven’t started building genuine client relationships by PQE 5, you’re already behind. The lawyers who make equity partner by their early thirties started cultivating those relationships in their late twenties, often through secondments, industry events, and strategic volunteering on matters where they’d gain client exposure.

The ‘Good Egg Test’ Nobody Tells You About

Being a consistently high biller isn’t enough. You must also pass what Armstrong Watson’s Andy Poole calls the ‘good egg test, demonstrating that you’ll be a collaborative, politically astute, and culturally aligned member of the partnership. This is where technically brilliant lawyers most often fail.

What ‘difficult’ or ‘not a team player’ usually means in practice:

- They challenged senior partners’ decisions too directly. Being right doesn’t matter if you make powerful people look wrong in front of their peers.

- They were insufficiently political. Partnership requires understanding and navigating firm politics. Pretending politics don’t exist is political suicide.

- They hoarded work rather than delegating. Partners need to leverage junior lawyers effectively. If you can’t delegate, you can’t scale, and you’re not partner material.

- They lacked strategic visibility. In larger firms, it’s insufficient to do excellent work quietly. You must strike a difficult balance to ensure the partnership committee sees your contributions without appearing self-promotional.

The good egg test is fundamentally about risk management. The partnership is asking: ‘If we make this person an owner of the business, will they enhance our reputation and profitability, or will they create headaches?’ The burden of proof is on you to demonstrate the former conclusively.

The Partnership Timeline Myth

Average partnership timelines have extended to nearly nine years but this statistic is deeply misleading.

It represents the average across all lawyers who eventually make partner and it doesn’t account for the far larger number who don’t make it at all. If 100 associates enter a cohort and 15 make equity partner after an average of nine years, what happened to the other 85? Some moved in-house, some joined smaller firms, some became counsel or non-equity partners, and some burned out. The ‘nine-year timeline’ only measures the survivors.

The timeline also varies dramatically by firm type. Magic Circle and elite US firms in London operate with longer tracks and lower success rates. Mid-market firms often have faster tracks but less lucrative partnerships. The brutal reality is that many associates spend 7-8 years pursuing partnership only to realise they’ll never receive the equity invitation.

Some firms are transparent: Freshfields shortened their equity partnership track from 10 to 9 years in 2021; others have moved from 9.5 to 7.5 years. But many deliberately maintain ambiguity, keeping senior associates in holding patterns because their billing hours remain profitable even when their partnership prospects don’t exist. The phrase ‘not quite there yet’ at PQE 8 usually means precisely that.

The Partner Attrition Nobody Talks About

Roughly 10–20% of newly promoted partners at major firms leave within two years of making partner. Which begs the question, why would someone fight for 8–9 years to make partner, finally achieve it, then leave within 24 months? The partnership promise rarely matches the partnership reality" to prime the reader before they hit the data.

What Associates Expected at Partnership

| The Reality That Drives Them Out |

A meaningful profit share and reward for years of loyalty | Non-equity PEP barely exceeds senior associate salary once capital contribution is factored in |

Continuation of high-quality billable work with added seniority | Relentless business development pressure — many discover they are temperamentally unsuited to sales |

A genuine long-term stake in the firm's future | Retention partnerships — elevated to prevent departure, not because equity was ever genuinely on offer |

Security and recognition after years of committed service | The partner title opens a more lucrative lateral market — and many take it |

Table 1: Common reasons for early partner attrition versus associate expectations.

I’ve placed dozens of newly promoted partners in lateral moves within 12–18 months of their initial promotion. The pattern is consistent: they made partner at a top-tier firm on unfavourable terms, then leveraged the title to secure equity partnership elsewhere with better economics.

The Lateral Partner Reality

Why Firms Hire Outsiders Over Homegrown Talent

London’s litigation market saw 35 disputes partner moves in 2025 through August alone, surpassing the 34 recorded in all of 2024. Of those moves, 83% were lateral hires, 14% were promoted to partner on arrival, and only 3% were in-house lawyers returning to private practice.

Think about what this means: firms are actively recruiting partners from competitors while simultaneously restricting internal promotions. Because lateral partners represent known quantities with established books of business. When Clyde & Co, CMS, Jones Day, Pinsent Masons, and White & Case are each adding multiple disputes partners, those are strategic revenue acquisitions, not rewards for internal loyalty.

The message to ambitious associates is uncomfortable but clear: your best path to equity partnership may involve leaving your current firm, building a portable book of business elsewhere, then returning laterally with proven credentials. Loyalty to a single firm throughout your career is increasingly economically irrational.

The Compensation Reality Nobody Explains Honestly

Equity partner compensation is more volatile, and more stratified, than most associates appreciate. The gap between top and bottom has never been wider, and where you land in that range is determined almost entirely by portable business and origination credit.

Firm / Category | Median / Avg PEP | Year-on-Year Change | Notes |

Slaughter and May | £3.75 million | Not disclosed | Highest in London market |

Macfarlanes | £3.1 million | +8% | Elite mid-market leader |

Linklaters | £2.2 million | +16% | Magic Circle |

Am Law 200 median | $1.05 million (est.) | +23% (UK top 50) | Broad US market |

UK top 50 bottom equity | £291,000 | −10% | Junior partners squeezed |

Table 2: Equity partner compensation benchmarks, 2024–25. Source: The Lawyer, published firm reports.

The formula is brutal: if you’re bringing in £10 million annually, the firm might pay you £2–2.5 million and keep the rest. If you’re bringing in £500,000, you might make £200,000 as a non-equity partner, barely more than you earned as a senior associate.

The capital contribution compounds this further. Many equity partnerships require new partners to contribute £100,000–300,000 as their capital stake. Most lawyers borrow it meaning you’re paying interest on a loan to buy into a partnership where your initial take-home may actually be less than your senior associate salary once debt servicing is factored in. Some firms are moving to tiered equity structures allowing gradual profit participation increases based on performance, which reduces the capital barrier while maintaining incentives around revenue generation.

The Questions You Should Be Asking

If you’re a senior associate contemplating partnership, here are the questions every candidate I work with should be asking of themselves and their firm:

- Do I actually want equity partnership, or do I want the title and prestige? Non-equity partnership gives you the title without the economics, business development pressure, or capital requirement. For some lawyers, that’s genuinely optimal.

- Can I realistically build a £1–2 million book of business? Be honest. Do you have the personality, relationships, and market positioning to generate substantial portable business? If not, equity partnership may be structurally unattainable regardless of your technical skills.

- Am I at the right firm for partnership? If your firm promotes 2–3 equity partners annually from a pool of 50 senior associates, your odds are 4–6%. Would you have better prospects elsewhere? Almost certainly yes.

- What are the actual partnership economics? Demand specifics: the capital contribution, the compensation structure, the profit distribution formula, and how lockstep versus eat-what-you-kill models operate at this firm.

- Who are my champions in the partnership? If you can’t name 2–3 equity partners with substantial influence who would advocate for your promotion, you don’t have a viable path. Build those relationships now or accept you won’t make it.

- What’s my Plan B? Too many lawyers pursue partnership single-mindedly for 8 years, then crash when it doesn’t materialise. In-house? Lateral move? Different practice area? Know your answer before you need it.

Why Some Brilliant Lawyers Don’t Make Partner (And Why That’s Actually Fine)

The partnership model evolved to serve firms’ economic interests, not lawyers’ career aspirations. It’s designed to identify lawyers who can generate revenue that significantly exceeds their compensation, then give those lawyers a share of profits while maintaining pressure to continually increase billings.

Many of the most technically brilliant lawyers I’ve known don’t make partner because they’re brilliant at law, not brilliant at business development. They can analyse complex regulatory frameworks, draft intricate transaction documents, or win seemingly unwinnable litigation but they can’t or won’t generate £1–2 million in portable business annually. And that’s actually fine. The legal profession offers multiple fulfilling paths beyond equity partnership: exceptional in-house roles with better work-life balance, non-equity partnership without business development pressure, general counsel positions, and increasingly, roles in alternative legal service providers and legal tech.

The key is making this choice consciously rather than spending a decade pursuing partnership only to realise at PQE 8 that you’re temperamentally unsuited to it, or that your firm never genuinely saw you as a future equity partner.

After thirteen years in this market, I’ve concluded that successful partnership pursuits require three things: realistic self-assessment about your business development capabilities, strategic firm and practice area selection, and the political acumen to navigate partnership dynamics. Technical legal brilliance is merely table stakes, necessary but wholly insufficient. The lawyers who make it understand partnership for what it actually is: a business ownership structure that rewards revenue generation, not legal expertise.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does one become a partner in a law firm, and how long does it typically take?

Making partner requires demonstrating three things beyond technical excellence: a portable book of business (typically £1–2 million for equity partnership at mid-to-large firms), the political capital of influential internal champions, and what the industry informally calls the ‘good egg test’, proof you’ll be a collaborative, commercially-minded co-owner rather than a liability. The average timeline across lawyers who eventually make partner is around seven to nine years post-qualification, though this figure only measures those who succeed. Magic Circle and elite US firms typically run longer tracks with lower conversion rates; mid-market firms can be faster.

How does one typically progress from associate to partner in a law firm?

Progression broadly follows four stages. As a junior to mid-level associate (PQE 1–4), the focus is technical excellence and building a strong internal reputation. From PQE 4–6, the priority shifts to client exposure; secondments, origination opportunities, and cultivating relationships that could eventually constitute a personal book of business. Between PQE 6–8, firms assess whether an associate has genuine partnership potential: meaningful portable business, a sponsor network within the equity partnership, and cultural alignment. At PQE 8–9+, the equity or non-equity decision is made. Crucially, the divergence between those who make partner and those who don’t often becomes apparent as early as PQE 5–6, particularly for women, where data shows a 4% gap opening at that stage that compounds significantly by PQE 10.

Is non-equity partnership worth pursuing?

Non-equity partnership is often, and perhaps unfairly, presented as a lesser compromise when firms want to retain billing lawyers without sharing meaningful profits. The honest assessment depends on what you want from your career. If you’re driven by autonomy, prestige, and title without the appetite for business development or capital risk, non-equity partnership may be genuinely optimal: you get the external recognition without the requirement to generate a self-sustaining book of business. If, however, you aspire to the economics of true partnership ownership; profit participation, capital appreciation, and the leverage that comes from an equity stake, then non-equity is a holding position, not a destination. The warning sign is firms that use non-equity partnership as a long-term retention mechanism with no realistic path to equity.

About the Author

Jason Connolly is CEO and Partner at JMC Legal Recruitment, specialising in partner-level recruitment, team moves, and law firm growth strategies across London and the South East. With thirteen years of experience in the legal recruitment market, Jason has placed hundreds of partners, advised countless associates on partnership strategy, and consulted with law firms on partnership structure and talent development. For confidential discussions about partnership opportunities, lateral moves, or strategic career planning, contact JMC Legal Recruitment.

Related Articles:

5 Reasons Partners Look to Leave

How to Become a Partner in a Law Firm